In animal industries all over Australia, pieces of animals’ bodies can legally be cut off, sliced open, and burned away… without any pain relief. If you cut the tail off a dog or cat, you could be prosecuted for cruelty. But for animals born into the category of ‘food’ rather than ‘friend’, painful surgical mutilations are a ‘fact of life’.

Governments in Australia have denied farmed animals the same legal protections from cruelty that apply to our pets. It’s legal and routine to cut off body parts like tails, teeth and testicles from cattle, sheep or pigs — with no pain relief.

Farming industries have been given exemptions to the cruelty laws that protect our pets. Among other things, these exemptions allow farmed animals to have bits and pieces cut off or burned into their bodies to make them fit into the monolith that has become modern-day industrial animal agriculture.

Many of these surgeries are not only entirely unnecessary but there is no legal requirement to provide animals with pain relief. This is despite easily applied pain relief products being affordable and readily available for use in Australia.

The drive to maximise profit and production in the meat, eggs and dairy industries has led to routine farming practices that completely disregard the welfare of animals. Practices that are anything but ‘normal’ have become the ‘norm’ in farming today.

Cows

Dehorning

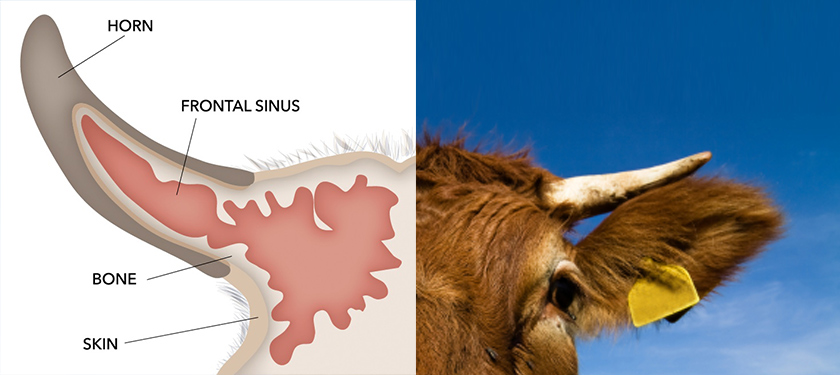

Dehorning is one of the most traumatic experiences cattle are forced to endure. Yet, there are no laws requiring them to receive pain relief at the early age when it is usually done. So, both male and female calves usually undergo this surgical procedure without anything to dull the pain.

When a cow is ‘dehorned’, her horns and the sensitive tissue near her skull are cut, sawn or scraped out. Anything from knives, wires, saws and shears — or even a ‘scooping’ implement — are commonly used to remove horns.